Hisaishi chose restraint. He had done everything for Ghibli from the otherworldly electronics of Nausicaä to the triumphant symphonic sweeps of My Neighbor Totoro, but he had never explored his first musical love: classical minimalism. Inspired by artists like Steve Reich and Philip Glass, he abandoned past productions’ grandiose orchestrations in favor of piano and spare accompaniment. This intimate change, Hisaishi said recently, “would be a chance for me to move myself close to what Miyazaki had intended.”

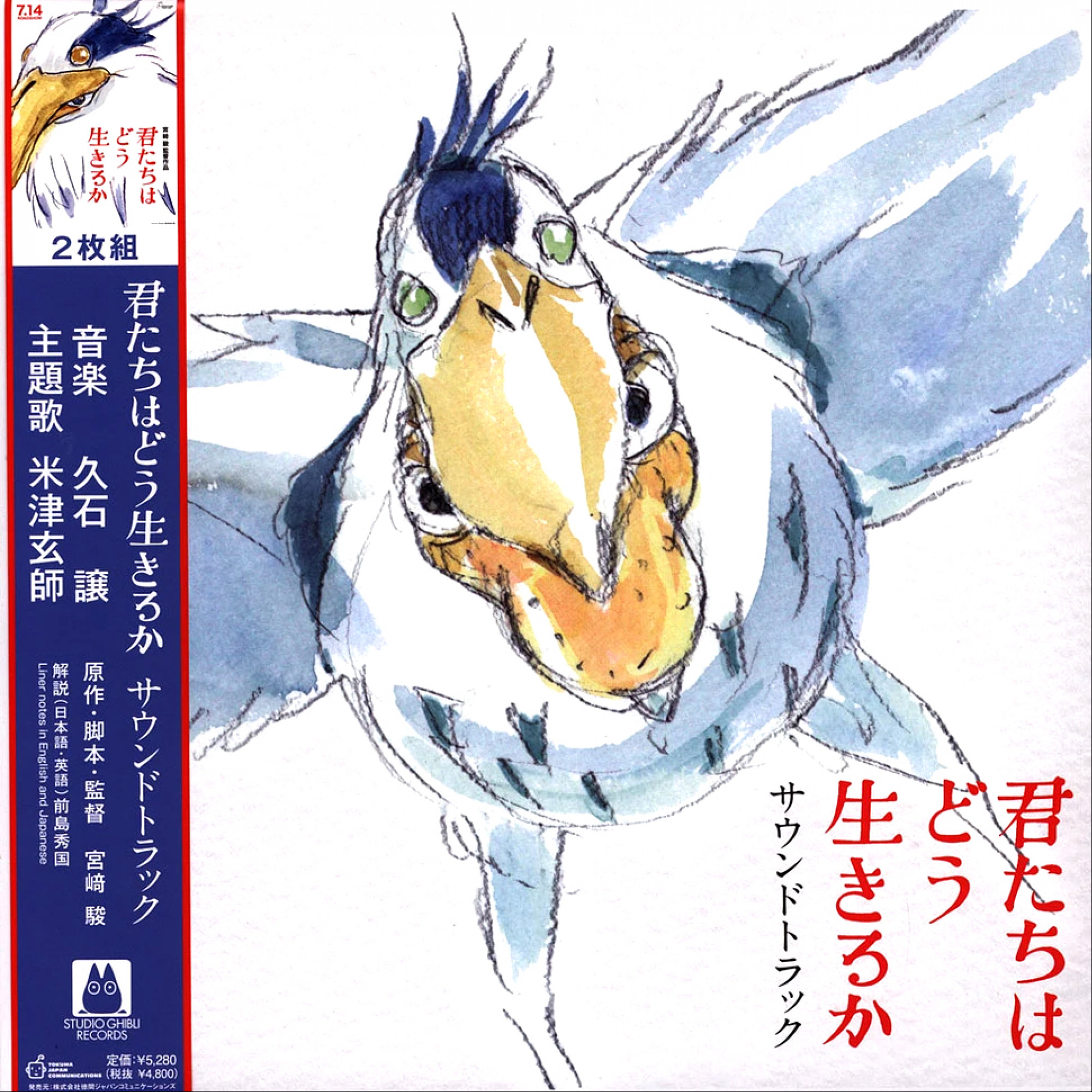

Heron is structured as two distinct chapters, and Hisaishi’s score mirrors its narrative arc. The film’s first hour, which depicts post-World War II Japan as Miyazaki remembers it, is primarily backed by Hisaishi’s piano and sparse arrangements. He plays with a stately grace on “White Wall” as the opening scenes unfold, bringing to mind the gentle lilt of Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies. When tension builds between the young boy and the titular gray heron, strings build to a sudden crest and fall away just as quickly. “A Feather in the Dusk” conveys mounting anxiety and temporary relief as man and beast lock in a standoff. The plucky strings of “Feather Fletching” bring a moment of levity before the oppressive threnody “A Trap” propels the action to its climactic turning point.

As the film transitions to its second act, the music opens up along with the scope of Miyazaki’s fantasy world. On “Ark,” Hisaishi adds wobbly pitched percussion to communicate the liveliness of the heron’s domain, while “Warawara” uses synthesized voices to underscore the whimsy of an eye-catching set piece. The main theme, “Ask Me Why,” is the strongest example of the way Hisaishi builds up musical motifs. The tender ballad - originally composed as a birthday gift for Miyazaki - appears on three occasions, accumulating momentum with each reappearance. By the time credits are ready to roll, the lightly accompanied piano composition has transformed into a celebratory orchestral swell, punctuating the decisive moment the protagonist gains his resolve.

The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s most personal work. It’s an unusually vulnerable window into the filmmaker’s life, featuring abstracted depictions of himself, his closest friend, and his late mentor at Studio Ghibli. Though his decades-long friendship with Hisaishi isn’t visible in the film, the score communicates it clearly. “What is most important to me is to compose music,” Hisaishi said in an interview. “The most important thing in life to Mr. Miyazaki is to draw pictures. We are both focused on those most important things in our lives.” Hisaishi pays respect to Miyazaki’s vision by creating his leanest work to date, giving those pictures plenty of room to move.

- Shy Thompson - pitchfork.com