The 33 Best Industrial Albums of All Time

In October 1976, the performance arts collective Coum Transmissions debuted Prostitution, an exhibition at the London Institute of Contemporary Arts. The opening night boasted a strip show in lieu of an introductory speech; alongside nude photos of Coum member Cosey Fanni Tutti, the troupe displayed used tampons, soiled bandages, and bottles of blood. The opening night marked the first performance from Coum’s ad hoc house band Throbbing Gristle, whose vocalist Genesis P-Orridge sang about castrating men and cutting the fetuses out of their pregnant wives. News of the show rang far. It was so disturbing to mainstream British culture that a conservative Member of Parliament declared Coum Transmissions the “wreckers of civilization.”

The ICA catalog from 1976 describes Throbbing Gristle as playing “DeathRock Music.” By the time the group had issued their first album, which included recordings from Prostitution’s opening night, they had settled on a different descriptor: “Industrial Music for Industrial People,” the tagline for their newly founded label Industrial Records. The term resonated on several frequencies: It spoke to the landscape of Throbbing Gristle’s native Hull, one of many English cities with architecture that had been transformed by the Industrial Revolution and then hollowed out by a decline in manufacturing work. It called back to Andy Warhol’s Factory, the studio where the New York artist smeared the imagery of capitalist mass production into the world of fine arts. Throbbing Gristle’s music often literally sounded like factory work, too, with its searing electronic noise and clattering percussion; however, P-Orridge’s squalling vocals tended to upend the image of the docile worker laboring away under capitalism. Androgynous, playful, and sinister, h/er voice traced a line of escape away from the suffocating constraints of h/er environment.

This was the sound of work, but it was also the sound of the refusal to work. Throbbing Gristle—and the many industrial acts who followed in their wake—funneled that metallic uproar into music that was not, at first, intended to move units. Caustic and provocative, it had little market value, but it found its intended audience. Across the Atlantic, a record store in Chicago called Wax Trax! started importing the sound of English disenfranchisement to the Midwest, a region similarly marked by industrial boom and decline. Run by Jim Nash and Dannie Flesher, who were business partners and a gay couple, Wax Trax! formed its own label in 1981. Its first pressing was a 7-inch single by the iconic drag queen Divine.

Throughout the ’80s, Wax Trax! would cement the sound of industrial with releases by both local and international bands like Ministry, Front 242, and My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult. The shop and label also served as a haven for a certain subset of Chicago’s queer community. “Wax Trax! was a community of people, all kinds of people, who didn’t feel like they belonged or were appreciated, or acknowledged or accepted in other places,” Julia Nash, Jim’s daughter, said in an interview this spring. “That label, it welcomed everybody. The gay community, I think it was just along the same lines of they were outcasts. Any of these little subsets were outcasts, and they all found a comfortable place and a home at Wax Trax!”

For people who were considered to be abject and disposable, cast outside the standard narrative of a heteronormative life, industrial music supplied an abrasive and volatile voice. In the ’80s, openly gay synthpop acts like Culture Club and Frankie Goes to Hollywood filled the radio, but their songs mostly homed in on undiluted pleasure and candy-coated escapism. It was fabulous, but for many, gay pop was not enough. It didn’t speak to the visceral anxiety of living as a queer person through the Reagan and Thatcher eras. It wasn’t nearly violent enough.

From its root, industrial music was informed by a queer and trans perspective. After Throbbing Gristle disbanded in 1981, synthesist Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson joined his boyfriend John Balance in the seminal act Coil. Genesis P-Orridge began h/er gender transition after marrying Jacqueline Breyer, known professionally as Lady Jaye, in 1995. For P-Orridge, transition was not just the expression of a long-dormant “true” identity but an art project in itself. S/he and Breyer both had surgery to resemble each other more closely in what they called the Pandrogyne Project.

Of course, industrial music also became a home to a torrent of straight male anger. Because no taboo was too extreme to be left off the table in the genre’s lyrics, many albums ended up recreating the patriarchal misogynist violence that still simmers barely masked beneath mainstream culture. There are artists on this list who sing about rape, and there are artists who have been accused of it. Art that sets out to disgruntle the powers that be always carries the risk of reinscribing the oppressions it tries to unsettle.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, as industrial got packaged for the mainstream by Nine Inch Nails, it ended up breeding with the synthpop from which it once stood so resolutely apart. It turned out that pop and industrial weren’t so diametrically opposed after all, even if Johnny Cash covering “Hurt” still sounds like a bad joke on paper. But industrial survived its sanitization. It oozed into the 21st century, where artists like Mica Levi, Pharmakon, and clipping. are channeling its chaos into some of the new millennium’s most exciting music.

Late capitalism continues its gallop toward oblivion, and full-time work is still draining out of the U.S. and UK with only the hellish gig economy to replace it. It’s as good a time as any to scream and bang household items together and overdrive a shitty amp. Industrial came out of a dark period whose shadow might never really ebb away. But it was proof that even in dire conditions, people who recognized capitalism’s hostility and heteropatriarchy’s limits could always band together and make a hell of a lot of noise. – Sasha Geffen

Controlled Bleeding: Knees and Bones (1985)

“It seems hard to believe that someone would actually have given us the opportunity to document this on record,” Paul Lemos wrote in the liner notes for a reissue of Knees and Bones, the debut full-length by his undefinable recording project Controlled Bleeding. Listening to this pulverizing early recording—a 50-minute storm of power electronics, initially presented on vinyl as two untitled pieces—and you can see what he means. The sonic equivalent of a blurry Xerox of a still from a horror movie, the record could have easily become just a curio: the harsh, murky noise album with the guy sticking rats into his face on the cover. Instead, it served as the tonal blueprint for decades of the group’s boundary-pushing music to come: a career that would cross over into jazz, progressive rock, dub, and beyond. Listen closely and you can hear the seeds for all those nightmares planted somewhere under the din. – Sam Sodomsky

Revolting Cocks: Beers, Steers + Queers (1990)

Originally founded as a three-way collaboration among Al Jourgensen of Ministry, Richard 23 of Front 242, and Luc Van Acker, Revolting Cocks shuttled in Scottish singer Chris Connelly to sing lead vocals in 1987, after Richard 23 skipped town. Landing in Chicago’s industrial scene was quite a culture shock for the young musician: “I was 21 years old, from a small town in Scotland, and I came to Chicago and entered this vortex,” he said in a 2008 interview. “It was the loudest, most violent music I’d ever heard and it seemed to me like the music of the future.” Jourgensen and company drew the newcomer deep into that vortex and, strange as it was to him, he thrived there. Connelly’s corroded wail makes Beers, Steers + Queers one of the most fun and irreverent records to come out of Wax Trax! “I’m in free fall and nothing holds me back,” he sings over a tightly wound bassline on “Razor’s Edge.” Harsher and more cohesive than RevCo’s 1986 debut Big Sexy Land, Beers, Steers + Queers serves up body-quaking beats with a venomous smirk. – Sasha Geffen

Pharmakon: Abandon (2013)

Margaret Chardiet was making noise around New York well before she was old enough to perform in its bars as Pharmakon. (In a 2013 Pitchfork interview, she noted, “I’ve been going to punk shows since I was a baby - my dad brought me to a Nausea show and threw my dirty diaper into the pit.”) She released several D.I.Y. 7-inches and cassettes before dispatching her first widely available record, Abandon, at age 22. The cover shows maggots crawling across her body, and she refused to use social media for promotion. The genuinely punk attitude was invigorating; it was like Chardiet had listened to No New York as a kid, thought it wasn’t heavy enough, and decided to confront this single-handedly.

Opening with a literal scream, Abandon showcases Chardiet's multi-octave voice, which can sound like it’s being filtered through a rusted fan; it’s a conduit for harrowing subject matter (death, failing bodies) and a cap on cataclysmic, unyielding atmospheres. Yet as chaotic and dense as her feedback grows, Chardiet’s a composer in full control of the world she creates: “Crawling on Bruised Knees,” for instance, isn’t about supplication. It’s about endurance and survival, until the inevitable rot. – Brandon Stosuy

clipping.: Splendor & Misery (2016)

Hip-hop and industrial are genres that share a parallel timeline and drum machines, but they veer significantly on the ethnic/racial makeups of band members and the root causes for their bleak worldviews. Quite a few rap groups, starting with Public Enemy and the Bomb Squad, started upbeat but went on to blur the boundaries between the genres with deeply noise-inflected tracks that can shut the party down rather than turn it up.

On the flip side, clipping. brought industrial hip-hop into the 21st century with Splendor & Misery, a noisy, operatic, Afrofuturist concept album that traces the downward spiral between the sole survivor of a spaceship slave rebellion and the AI brain that keeps the ship going. The L.A. trio features an experimental music PhD (William Hutson), a film composer (Jonathan Snipes), and a Tony-winning Hamilton star (Daveed Diggs); on this album, they also fold in a gospel choir, who deliver a fresh Nine Inch Nails-style grandeur to the group’s bleak sound. In form and content, the album contextualizes something missing from so much of industrial: that the capitalist system the genre has always critiqued—a power system that poisons our time, environments, and desires—can never be separated from its racial contextualizations. – Daphne Carr

Lords of Acid: Voodoo-U (1994)

Debuting with 1991’s Lust, Lords of Acid were best known for Belgian new-beat bangers with humorously filthy lyrics, the kind of club floor-fillers that hormonal drama club kids could put on their mixtapes. But the rampaging breakbeats, screeching-siren vocals, and double-barreled guitar and keyboard riffs of Voodoo-U were less funny and more frightening. The needles-in-the-red sound was as loud, lewd, and cavernous as the come-hither cover art by the artist COOP, which depicts a fluorescent-orange orgy in the bowels of Hell. Indeed, standouts like “The Crablouse” (a paean to the orgasmic prowess of pubic lice) and the explicitly witchy title track lent the demonic urgency of a summoning ritual to music for people who just really wanted to fuck other people in black mesh tops and vinyl pants. Go ahead, judge this one by its cover. – Sean T. Collins

Prurient: Pleasure Ground (2006)

The uncompromising New York-based multimedia artist Dominick Fernow is a one-man shop for industrial noise. Not only does he record as Prurient, he has several other monikers in the noise, minimalist electronic, and black metal scenes (see: Rainforest Spiritual Enslavement, Vatican Shadow, Ash Pool). He also runs the Hospital Productions label, which counts over 150 releases - most of them handmade and numbered, occasionally in an edition of 666.

For all that productivity and potential entry points, Prurient’s Pleasure Ground displays what Fernow does best in a shockingly succinct way. Its four long pieces of blown-out feedback elegantly mix industrial ice crystals with ambient rumbles and contact-mic slippages. The record ends with “Apple Tree Victim,” the most romantic harsh noise song you’ll ever hear. On it, Fernow’s shouts and howls ebb and flow against a mesmerizing, lapping tide of feedback, and it feels personal, universal, and ecstatic. That’s the key to unlocking his work: Fernow has a knack for obscured and unexpected melody, but more importantly, he imbues the loudest head-smashing noise with a quietly beating heart. – Brandon Stosuy

Chris and Cosey: Heartbeat (1981)

“Industrial music for us was about being industrious,” Cosey Fanni Tutti reflected of her time in the pioneering group Throbbing Gristle. “It wasn’t about industrial sounds.” Her point was proven when she and bandmate/partner Chris Carter formed a new duo after TG’s dissolution, veering away from the group’s harsh textures into lighter, more melodic territory. The music that comprises Heartbeat, their debut album, spans multiple genres - minimalist techno, spacey synth-pop, stretches of eerie ambience - while maintaining a rough, corroded edge. From the grinding pulse of opener “Put Yourself in Los Angeles” to the dazzling sci-fi title track, its vision and melding of textures influenced scores of electronic artists; it also provided a path for fellow industrial musicians to maintain their intensity while learning to lighten up and evolve. – Sam Sodomsky

Whitehouse: Erector (1981)

Is your landline slowly breaking? Are your robotic birds aggressively mating? Are you listening to your heartbeat as projected through a megaphone? Perhaps you are just playing Erector, the insane album by Whitehouse. The four-song record from the then-trio led by William Bennett deconstructed industrial and crystalized the subgenre he would later coin “power electronics.” Its sounds conjure technological death and ecstasy, like circuit boards have been let loose and only want to squeal. There is rhythm to be found, occasionally, but there are also such terrifyingly high-pitched noises that playing them feels like accepting a challenge. Stick with it and you’ll find yourself laughing in addition to wincing; no sounds this ridiculous should be taken so seriously. When Bennett yelps in pain behind a veil of noise, you know he’s only hurting himself. Have a masochistic little chuckle at his expense. – Matthew Schnipper

Death Grips: The Money Store (2012)

The revolution will not be televised because Death Grips just kicked in your TV screen and screamed “I’ve seen footage!” in your face. They are the revolution, born of industrial, noise-rock, rap, and the internet writ large. The trio’s debut album, The Money Store, was a coup for drummer Zach Hill, instrumentalist Andy Morin, and vocalist Stefan Burnett (aka MC Ride), who convinced L.A. Reid to sign their psychotic, scuzzy breaks to Sony. The production is full-throated and unsettling: Morin and Hill’s crowded mix of ’80s electronics and guttural beats sample the Beatles, Serena Williams screaming in a tennis match, audio bits from discarded cell phones found in the Saharan desert, and more. It’s a polemic against capitalism and violence that used a major label to disseminate aggressive agit-prop. The Money Store feels like kicking beehives and chewing glass, throwing yourself into a dirt pit, and listening to Gil Scott-Heron on DMT. It remains a power-grab by artists who never did it any way but their own. – Jeremy D. Larson

Throbbing Gristle: D.o.A: The Third and Final Report (1978)

D.o.A. was not Throbbing Gristle's final album, nor was it their third. The joke started with their debut recording, a mostly live piece they dubbed The Second Annual Report in an act of gentle trolling; it set the parameters for the band’s strange, loose, and darkly psychedelic music. D.o.A. crystallized them.

Comprising both group efforts and solo compositions from all four members of the band, D.o.A. dimmed the lights on what was already an incredibly haunted project. Scratchy sound collages, alternately placid and nauseous, bristle up against morose guitar-and-string sketches and pristine bleeps and bloops. This is electronic music made by artists who were deeply skeptical of technology, electronic music made by people who could already see the shiny new toys of the future leaching toxins into landfills. From blunt force trauma to third degree burns, D.o.A. offers plenty of grotesquely violent imagery, but it alchemizes these horrors into a paradoxical feeling of comfort. Here Throbbing Gristle made confrontational, acerbic, and often disgusting music feel, to some, like home. – Sasha Geffen

Nurse With Wound: Soliloquy for Lilith (1988)

In Jewish mythology, Lilith was the first woman, cast out of Eden for insisting on her equality with Adam. More commonly, she is recognized as the namesake for Lilith Fair, Sarah McLachlan’s female-focused festival that debuted in 1997. And in more squalid corners, she is the muse of Soliloquy for Lilith, the heavily droning ’88 release by Nurse With Wound, then the solo project of Steven Stapleton. This monologue takes on Shakespearean levels of lamentation, buzzing low across eight tracks and over two hours. Though Stapleton is no stranger to clamor, Soliloquy for Lilith takes a less-is-more approach to industrial music, inverting the loud horror of the genre into a more sullen fog of sound. It could not be further from the celebratory intentions of Lilith Fair; this sounds more like wherever she landed after Eden. In Judaism there is no heaven or hell, but this is the devil’s Muzak. – Matthew Schnipper

Tackhead: Tackhead Tape Time (1987)

In the mid-1980s, British producer Adrian Sherwood formed a constellation of bands with the house rhythm section of the pioneering hip-hop label Sugar Hill Records: drummer Keith LeBlanc, bassist Doug Wimbish, and guitarist Skip McDonald. Before long, they were playing together under at least four different band names, including Fats Comet and Maffia. Tackhead was the name the ensemble gave their heavier, more political work, the music they thought had no real commercial value. After Sherwood produced Ministry’s 1985 album Twitch, his predilection for rougher, coarser beats carried over to Tackhead Tape Time, the group’s debut studio album. Mixing samples, raps, drum machines, and live instrumentation, the LP ties together the threads connecting hip-hop and industrial, both genres created by artists in neglected post-industrial areas who dared to forge off-label uses for electronic music technology. Tackhead’s 1989 album Friendly as a Hand Grenade would polish the group’s multifaceted sound, but it’s their debut where you can most clearly hear their two parent genres knitting together into something new and vital, a fascinating chimera whose echoes can still be heard today. – Sasha Geffen

Pigface: Fook (1992)

The Pigface project began among backing instrumentalists on Ministry’s The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste tour, and was led by drummer Martin Atkins, who had already earned his underground bona fides with five years in PiL and Killing Joke. As can be the way with revolving-door projects, the group was dogged by inconsistency in both live shows and recordings, but Fook is a singular document of its success as a pressure valve for pop-minded, DIY-raised experimenters. Featuring a number of male and female vocalists, it somehow seamlessly moves from British pagan folk through frenetic electro hardcore and into the mid-tempo, snaking groove chants common to industrial, as best exemplified on the album highlight “Hips, Tits, Lips, Power!” Everything stays together with Atkins’ signature colossal drums, which bear a swinging musicality rare in the genre. – Daphne Carr

Swans: Greed/Holy Money (1986)

Desecration, self-loathing, flesh, power: This is the scripture of Swans, the infamously loud and transgressive New York noise band led for decades by Michael Gira. By Greed/Holy Money, they had blown up their sound - two bassists, three drummers, the vocalist Jarboe - to become a chamber group of hulking, post-industrial aggression, marching against the bull market of New York’s cocaine decadence in the mid-’80s. Swans’ songs, especially in this era, are interrogations: of status quo, of fetishes, of patience, of thresholds. With Jarboe’s cooling presence coming to the fore, and a cavernous production that reeked of basements and leather, Swans begin to reveal more layers to their compositions, their struggles with religion, and a contrast of light and dark to give their work a full dimension. Grimly, Gira’s allegations of sexual abuse later in his career - disappointing for an artist so fixated themes of domination and submission in his songs - now complicate Swans’ legacy, offering a darker coda still. – Jeremy D. Larson

Godflesh: Streetcleaner (1989)

As a teenager, Justin Broadrick brought chaos and destruction wherever he went. The precocious son of two members of the notorious late ’70s UK punk band Anti-Social, he was listening to Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music by age eight and pioneering grindcore as a member of Napalm Death in his mid-teens. For some musicians, assisting the birth of one genre would be enough. Yet Broadrick kept moving; there were more rules left to disobey.

Godflesh formed when Broadrick, then 15, joined a band that had been experimenting with a drum machine, and he quickly swapped out their tamer influences - Killing Joke, the Cure - with heavier stuff. After a self-titled EP, Godflesh sharpened their approach on 1989’s Streetcleaner, one of industrial metal’s most uncompromising and influential statements. Its nihilistic sound is defined by programmed drums, low and lurching guitars, and Broadrick’s inhuman howls of pain. As inspired as the music was, it was also a reflection of inner turmoil. “I couldn't come to terms with anything,” Broadrick reflected on his teenage years. “It was all a struggle, and I just wanted to lash out at every target I possibly could.” No simple bloodletting, Streetcleaner remains a masterpiece of precision: Broadrick obliterated everything in his path. – Sam Sodomsky

Mica Levi: Under the Skin OST (2014)

So much of industrial music is about power: the power imbalance between the individual and the larger social structure around them, the power dynamic between the punisher and the punished. British composer Mica Levi’s debut film score fits perfectly into this mold. Jonathan Glazer’s sparse and chilling Under the Skin follows an alien dressed as a woman who lures unwitting men to their death beneath an inky black pool, a reversal of the usual narrative of sexual predation. Like David Lynch’s 1977 surrealist horror breakthrough Eraserhead, whose score can be considered an industrial benchmark in its own right, Under the Skin features very little dialogue. In the space left wide open by that lack, Levi floats microtonal strings and pounding, insistent production. Everything in this soundtrack sounds like it’s being played urgently but wrong, carrying on in Einstürzende Neubauten’s tradition of scratching at things until they sound good. And the menacing drone suspending Levi’s minimal compositions hearkens back to Nurse With Wound’s calmer offerings. It’s fitting that one of the 21st century’s boldest and most searing industrial compositions is the theme song for a woman who rends men for their meat, turning the meet-cute scenario the alien deftly exploits on its cracked and bleeding head. – Sasha Geffen

Nine Inch Nails: The Downward Spiral (1994)

Here’s Trent Reznor at his hardest and softest, playing both the big man with a gun and the small man immobilized by existential despair. While Pretty Hate Machine would set the template for Reznor’s industrial pop and introduce the genre to the mainstream, The Downward Spiral pushed him to the edges of his range. Pummeling, full-body beats shudder through barnstormers like “March of the Pigs” and “Mr. Self Destruct,” which manage to carry violent rage into choruses that function, effectively, as pop hooks. The distorted bass/snare throb of “Closer” is by now as instantly recognizable as the refrain’s bestiality-brushing lyrics.

But The Downward Spiral doesn’t just show off Reznor’s talent as a beatmaker; it leaves space for him to be soft, too. “A Warm Place” and “Hurt” lace overwhelming pain into stirring melodies, presaging the knack for atmosphere that Reznor would bring into his film compositions. As Nine Inch Nails, he often exacerbated the image of the angry white American man to the point of parody, playing out the brittle frustrations of a character who doesn’t have the resources to name his pain. On The Downward Spiral, he expends a little color on the pain behind the rage, fleshing out the archetype he’d spend a career illustrating. – Sasha Geffen

Skinny Puppy: Too Dark Park (1990)

Vancouver’s Skinny Puppy are the germinal group of 1980s industrial music, a revolutionary band that pushed the limits of their voices, bodies, and instruments in ways that are still fruitful 40 years later. Their sound came from two gems of 1970s UK underground, new wave synth pop and industrial experimentalism, and offered forth a string of jagged, lo-fi groovy singles that dominated alternative ’80s dance floors. An early signing to Nettwerk Records, Skinny Puppy also delivered to the masses two iconic musician/performers, cEvin Key and Nivek Ogre, whose powerful, shocking stage shows would define industrial of the decade.

While Skinny Puppy’s early-’80s hits need to be heard, Too Dark Park is their album made for deep listening. It’s the band’s distillation of their earlier darkwave dance floor vibe, with a clear desire to move forward into denser territory; it’s also their pledge to end the toxic environment of their Rabies studio sessions. Also, the 1986 addition of classically trained pianist Dwayne Goettel allowed the group to realize thicker, more fully scored compositions. Too Dark Park is a collage of horror film samples, eerie synth pads, doom, pop-oriented drums, and layers of vocal and instrument noise. Although guitar does appear throughout, it’s consciously understated, and Nivek Ogre’s ragged baritone growl is deeply effective sotto voce, his disenchanted narrator cataloging the wreckage of paradise due to ecological disaster. As was a theme for many an industrial artist in the ’90s, Ogre also dwells on the self-destructive spiral of heroin use in “Spasmolytic,” a track as close these former dance floor dominators get to pop, an anxious, sneering missive with monstrous, sexy drums. Just as industrial was about to become a sensation in America, not least from their efforts, Skinny Puppy were indeed kicking the pop habit and heading back into the scene’s underground. – Daphne Carr

My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult: Confessions of a Knife... (1990)

The Thrill Kill Kult advocated for drug use and Satanic worship in their songs to the extent that they landed on Tipper Gore’s hit list. The Chicago band’s gleeful sleaze and overt expressions of queerness peaked with Confessions, an album that didn’t take anything but the dance floor seriously. If Ministry hadn’t disavowed their earlier synth years so vehemently, they might have sounded something like this, a merge of clubby funk and synths with pounding bass, distorted and sneering vocals, and clanging percussion. Overt disco influence, with the repetition and dialogue sampling of industrial, completed the heady formula.

After releasing Confessions, Thrill Kill Kult would move closer to techno and find an MTV hit “Sex on Wheelz,” but several of their biggest club tracks are here. “A Daisy Chain 4 Satan” locks in their formula: the unvarying bassline repeats from beginning to end, singer Groovie Mann wails in pure torment under perky synths and vocal samples of a flower child rhapsodizing about drugs. It all cuts deep. – Susan Elizabeth Shepard

SPK: Leichenschrei (1982)

SPK stood for many things - their Meat Processing Section 7'', released on Throbbing Gristle’s Industrial Records, was credited to Surgical Penis Klinik - but they were more frequently known as Socialist Patients Kollektiv, a name they borrowed from a German patients’ collective that believed mental illness was a form of protest against capitalism. Graeme Revell, the leader of SPK, actually worked in a psychiatric ward in his native Australia before moving to the UK, and he makes that experience sound terrifying on Leichenschraum, with undulating synths and shuddering electronic percussion suffused in found-sound noises and disembodied speech. (“I remove the rectum itself,” narrates an impassive voice at the beginning of “Post-Mortem.”) By today’s standards, the group’s shock tactics can seem hackneyed and even tasteless - the original album cover featured a face burned by napalm - and the sensationalistic depiction of mental illness, likewise, feels exploitative and lacking in empathy. Still, in terms of pure, visceral horror, this is as thrillingly bleak as industrial music gets. – Philip Sherburne

Foetus: Nail (1985)

By the time he released Nail, the Australian-born musician JG Thirlwell was living in New York, going by the alias Clint Ruin, and releasing music under the name Scraping Foetus Off the Wheel. (This was his second “band” name to include the word Foetus, after You’ve Got Foetus on Your Breath.) His fourth full-length album in the Foetus universe, Nail, drew a smorgasbord of genres down into a demonic vortex. At times, Thirlwell sounds like he’s doing vaudeville in hell; at others, he’s preempting the semicomic vitriol that Trent Reznor would drag kicking and screaming into the mainstream.

According to Thirlwell, this is what it sounded like in his head at the time. “I’m so close to this record - it’s like I’ve cut off a leg and put it in the record stamper,” Thirlwell said in a 1985 interview with NME. “I think it’s an effort to articulate myself and make an aural equivalent of myself which has been successful.” It sounds exhausting, having that much stuff swimming in your skull at all times, but it’s also a thrill to go along for the ride. Few industrial artists had the patience or the will to commit fully to this much sweeping operatic bullshit. Nail stands out as one of Foetus’ most adventurous releases, and also one of the most perversely fun. – Sasha Geffen

Einstürzende Neubauten: Kollaps (1981)

erlin was a strange place in 1981 - a divided city stuck in the middle of Europe, a cul-de-sac of the Cold War. Yet for the countercultural youth of West Berlin who convened around the concept of Geniale Dilletanten (“genius dilettantes”), it was a place of radical possibility. Einstürzende Neubauten summed up the anarchic spirit of the era; their debut album, Kollaps, utilized an array of power tools, scrap metal, and electronic techniques to wed primal rhythms with harsh noise, overlaying it all with Blixa Bargeld’s larynx-shredding vocals. (Their name, fittingly, translates to “collapsing new buildings.”) The record is, by turns, brutal and unsettling, both literally industrial - just check the 35 seconds of jackhammer that opens “Steh auf Berlin” (“Rise Up Berlin”) - and faithful to industrial music’s larger aim to filter the strategies of the 20th-century avant-garde through the structures of popular music. It’s a riveting fugue of clang and crunch. – Philip Sherburne

Nitzer Ebb: That Total Age (1987)

Inspired by the likes of Killing Joke and Bauhaus, Nitzer Ebb’s earliest work is fueled with a heavy, sweaty youthful energy. Vocalist Douglas McCarthy chants slogans like “let your body burn,” coming off like an industrial aerobics instructor, while Vaughan Harris offers a bed of steady bass and manic, repetitious synths and percussion. (The Essex group has featured a rotating cast of drummers since they started, with McCarthy and Harris as the essential core.)

The band released early singles on their own Power of Voice Communications label, but Mute put out their 1987 debut, The Total Age, a collection that distills their aesthetic to its synth-punk components. Nitzer Ebb opened the European leg of Depeche Mode’s Music for the Masses tour that same year, but this was less about stadiums and more about late-night clubs where a few folks are drunk and fucking. (That said, their essential “Join in the Chant” did make it to No. 9 on the U.S. dance chart.) The group has since exhibited big-league staying power, reforming in 2007 and still performing today. They really showed their hand on this record, though, and what they went on to do never quite reached the dizzying, exhausting heights of these adrenaline-drunk anthems. – Brandon Stosuy

KMFDM: Naïve (1990)

Naïve established KMFDM as the party band of industrial, combining hip-hop beats and metal riffs into deep, big-beat anthems. From the dance floor to the mosh pit, the German band owed equal debts to techno and metal, and their noisy, surprisingly catchy synthesis of sounds drew fans from both sides of the aisle. Naïve was not without its controversies - an uncleared sample from “Carmina Burana” in “Liebeslied” resulted in the original album being pulled from shelves three years after its release - but KMFDM didn’t need to steal any elements of their palatable sound as it edged into the mainstream. The title track illustrates KMFDM’s ability to write a pop hook, the secret weapon that sweetened the squalor. The humor in their work - from their self-deprecating lyrics to letting journalists believe their name was an acronym for “Kill Mother Fucking Depeche Mode” - set them apart from their self-serious industrial peers, too. But as bandleader Sascha Konietzko told journalists in the ’90s, all these relatively cheerful elements were a distraction from the band’s double-bummer burden: being both German and an industrial band. – Susan Elizabeth Shepard

Killing Joke: Killing Joke (1980)

Killing Joke’s self-titled debut LP left its sooty fingerprints all over goth, metal, post-punk, and eventually alternative. But from vocalist Jaz Coleman’s growling, distorted doomsaying, to the alternating groove and grind of the rhythms and riffs, to the high-contrast image decay of the cover (Northern Irish rioters fleeing the British Army, in case you thought this band was fucking around), the album left its deepest marks on industrial. Killing Joke’s ability to harness percussive, electronically augmented cacophony and political despondency, then deploy it via headbanging and bodyslamming, reads like a blueprint for the future crossover success of Nitzer Ebb, Ministry, and Marilyn Manson. It’s the witchy presence of Coleman - an onstage wildman whose lyrics repeatedly conjure the old world’s terrible death, necessary so something new can begin - that makes Killing Joke a lynchpin of the genre in its own right. – Sean T. Collins

Nurse With Wound: Homotopy to Marie (1982)

If the caricature of industrial music is one of noise and fury, Homotopy to Marie stands out for its penumbral hush and sustained sense of dread. Nurse With Wound’s fifth album was crafted over the course of a year, in the dead of night, and the gothic mood permeates: bandleader Steven Stapleton stitches together bowed gongs, pitched-down moans, ethnographic recordings, snippets of film dialogue, and blasts of pure noise into long, meandering explorations of the dark side of musique concrète. It amounts to an uncanny dreamscape, a shadow play of distorted shapes whose deeper significance lingers teasingly just out of reach. – Philip Sherburne

Nine Inch Nails: Pretty Hate Machine (1989)

Pretty Hate Machine brought industrial to the masses, and is a great unifier of them. It’s a concise expression of all of Trent Reznor’s disparate strengths as a songwriter and frontman: The melodic melancholy that would later make him a go-to film composer; the love of larger-than-life stars like Freddie Mercury and Prince that lent his music a slinky fluidity; the tinnitis-inducing guitars that got goths invited to the Headbangers Ball; quotes from Clive Barker short stories, because game recognizes psychosexual game. It blends external sources of rage and angst, from the government to the capitalist class to traitorous lovers, into one big catharsis, with still-blistering self-hatred thrown in for good measure. – Sean T. Collins

Front 242: Front by Front (1988)

Electronic body music - the industrial subgenre that merged punk aggression with club-friendly beats - exploded on Front by Front. Front 242 had used the term on their previous album, but “Headhunter V 3.0,” which pulls off the feat of being an industrial hit with overlapping group vocals, brought EBM into the mainstream. Paired with the mandatory grainy Anton Corbijn video required of serious electronic bands at the time, it propelled the album to becoming the biggest seller Wax Trax! records had ever seen. And its B-side, “Welcome to Paradise,” is the pinnacle of industrial music’s frequent practice of sampling televangelists.

The fact that Front 242 features multiple vocalists, sometimes singing melodically complex parts, set them apart as much as the precise programming and relentless beats of their music. The energy level hits somewhere between “drill instructor” and “aerobics class” for much of the album - relentless and possibly malicious, yet perfectly attired and eliciting compliance. Both inspired by and critical of the institutions around them - the church, the military, capitalism - Front 242 still feel forward-looking. Their combination of sampling and electronics feels prescient; their militaristic rants don’t feel dated one day. – Susan Elizabeth Shepard

Ministry: The Land of Rape and Honey (1988)

Many a synth band bridged into industrial by harshing their production: boosting the drums, aggravating the vocals, sprinkling in samples of dark pop culture. Ministry’s contributions to this formula were the sneering, atonal distortion of hardcore punk and the brutal heaviness and speed of thrash metal. It happened first on The Land of Rape and Honey, the first of three albums from the band’s golden age, which also marked singer Al Jourgensen’s shift from the affected British accent of the group’s early sound to the demon-croak master of chants that became his signature. Ministry’s blend of industrial and metal offered extreme music a new palette of sounds, and it also influenced “serious” mainstream metal and rock bands to rethink the keyboards they’d distanced themselves from over the past decade. It was also great to dance to; its opening track and early hit “Stigmata” remains a goth night staple.

This was the first of Ministry’s many album titles that flouted taboos, just one more bad joke in a genre replete with heterosexual white men citing free speech and political satire to justify lyrical fantasies about personal, sexual, political, and religious violence. As industrial was rising in the American consciousness, critic Ann Powers unpacked this in a famous essay on “violator art.” From today’s lens her final argument is up for debate: “Not all art that claims to be transgressive is worth caring about. But you can’t tell the bullshit from the real by setting moral standards. You have to set artistic ones.” But even by the standards of the time, Ministry’s lyrical “art” was questionable. The power of their sound, however, is undeniable. – Daphne Carr

Cabaret Voltaire: Red Mecca (1981)

The third leg of the founding trinity of industrial that also includes Throbbing Gristle and Einstürzende Neubauten, Cabaret Voltaire tend to get the least credit of those acts because they stayed so briefly in the scene. Starting out as a more straightforwardly post-punk group, the English band later transitioned into a synthpop New Wave act, the form in which they prospered. But still, in that short tenure, they made this paranoid, claustrophobic masterpiece.

From the nearly funky “Sly Doubt” to the proto-EBM “Spread the Virus,” the seeds of a dozen industrial bands are here, buried in seriously lo-fi production and primitive electronic percussion. Its center is the bleakly gorgeous and expansive “A Thousand Ways,” a masterpiece that cracks the 10-minute mark. Beginning with dramatic organ chords that continue throughout, the song is built on a thin, metallic rhythm generator and a contrastingly full and warm bassline; its sprawling length, guitar skronk and drone suggest a connection to Krautrock epics. The apocalyptic themes that drive Red Mecca expanded on the band’s fascination with religious fundamentalism, which was said to be inspired by the American evangelicalism the band encountered while touring the U.S. While often lyrically inscrutable, titles like “Spread the Virus” suggest a conception of religious fundamentalism around the world as destructive, unstoppable forces that seek to replicate themselves. Skinny Puppy, Nine Inch Nails, and a good portion of the 1990s Warp Records roster would still be picking up these threads of ideas a decade later, but the eerie beauty here is irreplicable. – Susan Elizabeth Shepard

Coil: Horse Rotorvator (1986)

Horse Rotorvator is industrial music’s Trojan horse. After the freeform drones of Coil’s debut EP, How to Destroy Angels, and the glowering Scatology, the band pivoted toward an almost shockingly palatable sound with their 1986 album; its first two tracks pair dance-driven drum programming with bright synths and clanking keyboard samples reminiscent of Depeche Mode’s 1984 smash “People Are People.” (Bandmates Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson and John Balance had a much less mainstream pedigree, though, as former members of Psychic TV and, in Christopherson’s case, Throbbing Gristle.)

Beneath the album’s shiny veneer, though, lay much darker vistas: “Ostia,” about the murder of the Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini, folds in the sound of crickets recorded at Chichen Itza, a pyramid with a history of ritual human sacrifice. The funereal “Ravenous” is a patchwork of Gregorian chants, Ennio Morricone-inspired Western riffs, and what may be trumpeting elephants; the serrated, guitar-like tones and turgid drumbeat of “Penetralia” summon the harshness of early Swans or Big Black and add freeform sax skronk. “Circles of Mania” made explicit the album’s themes of death and regeneration, a theme fundamentally rooted in the album’s era: “I saw a lot of the people I knew who were dying of AIDS at the time,” Balance told The Wire in 1998. “That’s how my mind could deal with it, by believing that they’d died to keep the world turning.” – Philip Sherburne

Einstürzende Neubauten: Halber Mensch (1985)

Einstürzende Neubauten translates to “Collapsing New Buildings,” and the German group likewise created music with scrap metal and standard-issue tools. Once, they tried to take apart a stage in London with drills and jackhammers. Led by the charismatic, caterwauling vocalist Blixa Bargeld, the group felt like they were simultaneously building and destroying themselves on their first two albums, moving from the spare, feedbacking free-punk clang of 1981’s Kollaps to the more expansive glass-shattering of Zeichnungen des Patienten O.T.

Halber Mensch was their first collection with an outside producer, Gareth Jones, who’s also worked with Depeche Mode, Wire, and Erasure. Neubauten are more deeply demolishing than any of those groups, but Halber Mensch is a rhythmic, oddly danceable record that comes across equals parts operatic and apocalyptic. The collection includes everything from a cappella chants to what sounds like a tap-dancing, finger-snapping Germanic West Side Story riff, but it also edges into slinky electronic dance, a torch song performed with broken glass, and the sound of a literal kitchen sink. It’s sprawling and squalling, a bit like when an abstract artist suddenly gives you something figurative before smashing back to splashes and splatters. It gave a hint of shinier things to come, but Neubauten never really stopped eviscerating music. – Brandon Stosuy

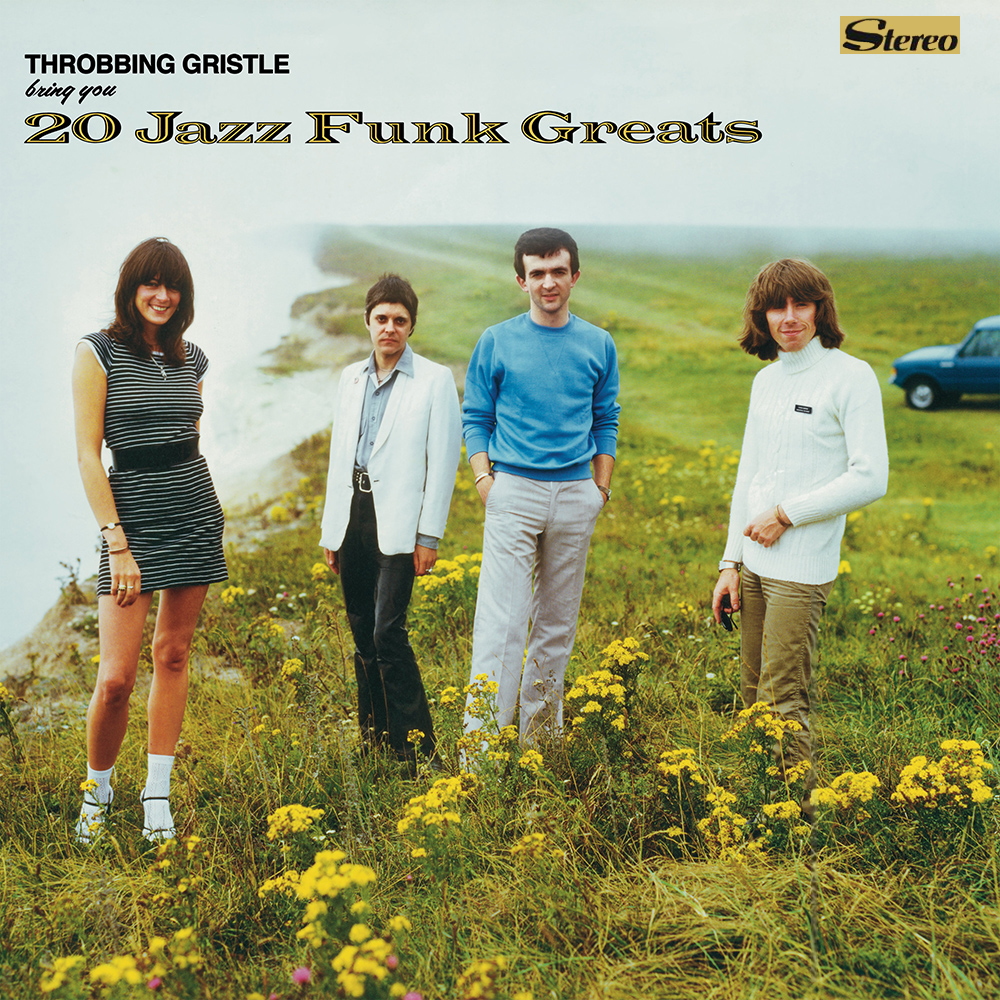

Throbbing Gristle: 20 Jazz Funk Greats (1979)

Throbbing Gristle’s third studio album, 20 Jazz Funk Greats, is their perfect manifesto. Starting with its eerily bucolic cover art and the false advertising of its title, the record is a collagist landscape of fucked-up rhythms, evocative and intense lyrical imagery (such as “I’ve got a little biscuit tin/To keep your panties in/Soiled panties”), and severed noise. As a band, Genesis P-Orridge, Cosey Fanni Tutti, Chris Carter, and Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson created an uncanny mix of haunted chants, slurs, and spoken howls amid drifting homemade cassette samplers, phasers, warped cornet, programmed drums, and dislocated guitar. Each member of Throbbing Gristle was a distinct figure, contributing to the charismatic whole. But it always felt like cheating to focus too much attention on who was doing what at any given time. The magical mashup and unknowability was part of the pleasure.

And part of the shock: Just as the listener is getting used to living in Jazz Funk’s disemboweled music box, the band serves up the shiny, thumping electro disco of “Hot on the Heels of Love,” anchored in Fanni Tutti’s breathy whispers, a dance-floor snare, and delicate vibraphone notes. They founded their own world - creating a cracked framework for industrial music, populating it with their own squalor and later side projects, and then tearing it apart with a smile. – Brandon Stosuy

- pitchfork.com