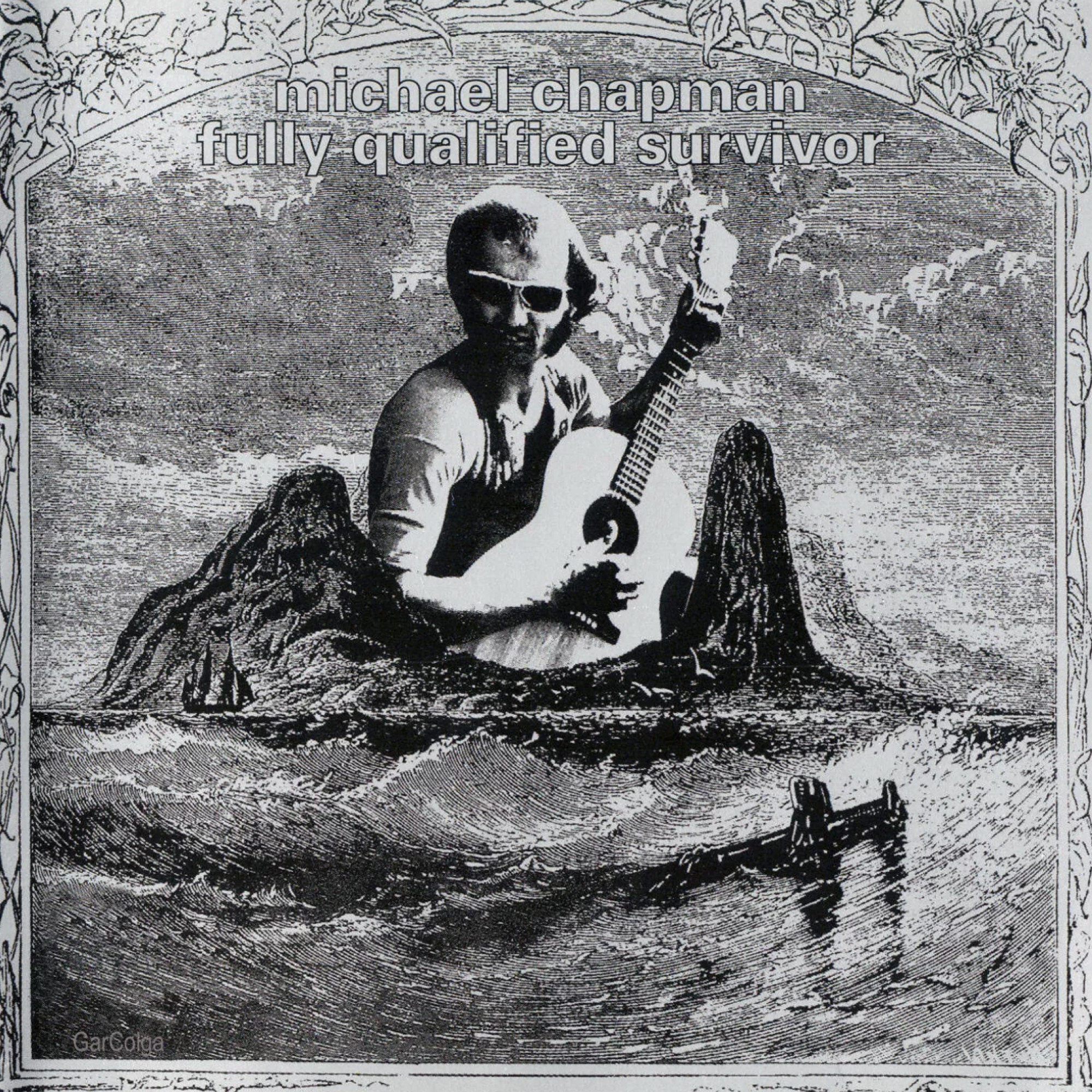

After the critical acclaim Michael Chapman received for Rainmaker in 1969, he followed up quickly in early 1970 with Fully Qualified Survivor, a record more adventurous and haunting than its predecessor, with added production flourishes and equally strong songs. Fully Qualified Survivor is the album that established Chapman as a folk troubadour. Leaving the guitar pyrotechnics largely locked in a shed, Chapman concentrated instead on his songwriting skills, and the sacrifice -- for this record anyway -- paid off. Leaving the lead guitar credits to a fellow Hull-man, Mick Ronson (who got his gig with David Bowie as a result of his playing on this album), with Rick Kemp making a return as bassist and Barry Morgan on drums, Chapman relied on no less than Paul Buckmaster -- then beginning to work with Elton John, among others -- to employ and arrange a small string section to fill out the songs. It paid off, netting him his only chart hit, "Postcards of Scarborough." However, the disc's opener, "Aviator," is the song that best embodies the spirit of the songwriter and album better than anything else on it. Aviator begins with a lilting violin entwined around a cello and a strummed guitar. Chapman intones his lyrics as a world-weary traveler who has come to the end of his days and looks back on the things he has seen, loved, and lost. The song has no refrain, and is sung like a poem, with stunning violin fills swooping and sweeping all over the place, and with the cello and Kemp's bass playing counterpoint to one another in a melancholic melody full of pathos and verve. Some of Chapman's finger-wild guitar shine is displayed in the laid-back rag "Naked Ladies & Electric Ragtime." Ronson, for the very first time on a recording, got to showcase his lead-guitar skills on the sweeping "Stranger in the Room," a meld of folk and rock that holds one of the best crescendos in the history of either music. Chapman's material is dark, unrelenting, and as seasoned as a seaman in its distance from the object of his distaste and affection. But it's the next track that held the magic for tens of thousands in the U.K. and has become Chapman's albatross. "Postcards of Scarborough," with its languid, acoustic guitars strummed and fingerpicked for a full minute before the strings and vocal kick in. It's a song that evokes the memory with all its bittersweet power. The lyrics are so picaresque the listener can "see" the scene unfold in the singer's mind. The stunningly long refrain is punctuated by a swell of strings and Rono's leads and gets carries into emotional-overload territory. Once you hear this song, with its notion of the protagonist having "Postcards from Scarborough to keep in my mind/To hide from where I've been/To help remind/Of time passed and time passing," you'll not be able to get its brokenness from your mind, nor will you know the how and the why of all that's transpired. There's regret and resignation, and perhaps the scant trace of bitterness, but no longing or yearning. It's Zen-like in its acceptance. The rest of the disc is solid as well, from the rocking, crackling "Fishbeard Sunset" to the poetic and opaque "March Rain" to the darkly hunted "Kodak Ghosts." It digs deep into emotional territory by way of tight, almost suffocating songwriting and killer arrangements, making this one of the defining Brit folk-rock albums of the period. It holds up well in the 21st century as a true testament to the excellence of Chapman's craft.